by Richard Olivas

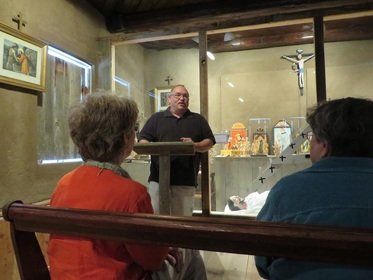

On Ash Wednesday, February 18, 2015, Ernesto Ortega of La Madera, New Mexico made a presentation at Adams State University as part of their Colorado Field Institute, Winter Lecture Series, about the Penitentes of Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado. Ortega has been a hermano penitente for over 50 years, has a BA in history, and is a retired National Park Service employee.

The presentation began in complete darkness as Ortega, joined by the hermanos from the Morada de San Francisco, chanted the haunting alabado melodies of La Misión and Madre de Dolores. He went on to explain the 400-year history of the Moradas in our culture. He also spoke eloquently about the continuing lack of understanding caused by misinformation and sensationalism that has colored the “American” comprehension of the Penitentes and our Manito culture since the middle of the 19th century. He then went on to explain the relationship between the Church and the Sociedad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno into the modern era. His presentation was very well received.

It is a known fact that on 29 April of 1598 Juan Pérez de Oñate went off to pray and practice bodily mortification on the eve of the entry of the colonists into what would from then on be called El Reyno de la Nueva Méjico, now New Mexico and southern Colorado. It appears that only a little vein of that practice survived over the course of the next century. Beginning, though, in the mid 18th century the annals of the priests record a lay organization that had taken hold in the remote areas of New Mexico where there were no priests available to provide Mass, baptisms, weddings, and funerals for the faithful.

According to Ortega, as the Franciscans left Nuevo Mexico and the Diocese of Durango, Mexico took over their responsibilities, the people were left without benefit of much clergy for several decades. It may have been a few priests who gave instruction to the first penitente recruits about the Via Crucis, the Tinieblas, and the Alabados. These practices were focused on the suffering of Jesus and Mary which defined the Cofradia de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno, founded in 1600, that by then existed in both Spain and New Spain (Mexico).

We also know that the Cofradías in Spain and in Mexico have since then each evolved into very different organizations then what we know here as the Penitentes. Today, in many cities of Spain you will see the Cofradía de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno in red robes and pointy red hoods during holy week as they carry the figure of the wounded Christ and sing saetas. Many of their saeta melodies are reminiscent of the alabado melodies still sung in New Mexico and Colorado.

Ortega explained that the word “alabado” comes from alabar – a Spanish word taken from Arabic which means: to give praise to God; to Alláh. He went on to explain that even the melodies of the alabado hearken back to the early Spanish Jews and Muslims in style, cadence, tone, and ornamentation.

After the American takeover of New Mexico in 1846, the Catholic Church of St. Louis, Missouri, under the guidance of French priests, took over New Mexico. Shortly thereafter a Harper’s Bazaar reporter learned of the Penitentes and proceeded to participate in and take photos of the hermanos engaged in their rituals. The article painted the hermanos, and indeed all Manitos, as uneducated, bloodthirsty throwbacks whose life in the desert had caused them to invent rituals that led inevitably to blood sacrifices.

The bishop, Jean Baptiste Lamy, had struggled to get Manitos to accept his authority. The priests and people remained faithful to Bishop Zubiría of Durango. The scandalous article about the Penitentes angered Lamy and eventually caused him to harshly sanction the moradas. This forced the Penitentes underground where they continued to practice. Acceptance of them as a Catholic organization has been slow. Not until fellow manitos, Archbishop Roberto Fortuna Sánchez of Santa Fe and Bishop Arturo Tafoya of Pueblo, in the 1980’s, were the Penitentes given full recognition.

Our ancestors left their homeland to find a better life. In the midst of surviving in a harsh kingdom far removed from their native land, and intermarrying with new peoples, they carried with them their culture and their faith and passed it on so that 400 years later we might live out the legacy they left us. Proudly, yet humbly, the hermanos of the Morada de San Francisco invite you to join them at 2 p.m. every Friday during Lent to rekindle that legacy.

Our ancestors left their homeland to find a better life. In the midst of surviving in a harsh kingdom far removed from their native land, and intermarrying with new peoples, they carried with them their culture and their faith and passed it on so that 400 years later we might live out the legacy they left us. Proudly, yet humbly, the hermanos of the Morada de San Francisco invite you to join them at 2 p.m. every Friday during Lent to rekindle that legacy.